Is the 'Michigan Left' the Solution to the Typical Stroad?

Screenshot Streetcraft/YouTube

Get The Drive’s daily newsletter

The latest updates on cars, reviews, and features.

From Henry Ford’s Five-Dollar Day to its unrivaled manufacturing contributions supporting Allied forces during World War II, Michigan has been a center of American industrial innovation for decades. However, despite its 20th-century supremacy in mechanized production, Detroit boasts surprisingly few distinctive and well-known inventions. In fact, the automobile was not originally invented here; Hank and his team simply discovered how to produce it more efficiently than anyone else. Perhaps its most famous export—Motown Music—only shares a name with the automotive industry. Enter the Michigan Left: This is less a planned creation and more a fortunate offshoot of an outdated transportation strategy that left southeast Michigan with one of the largest yet underused road networks in the nation.

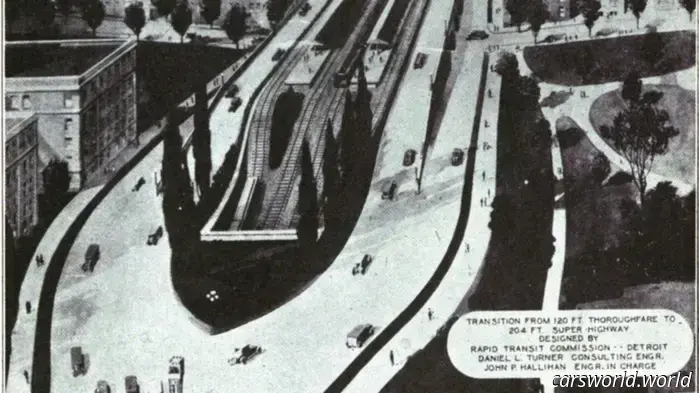

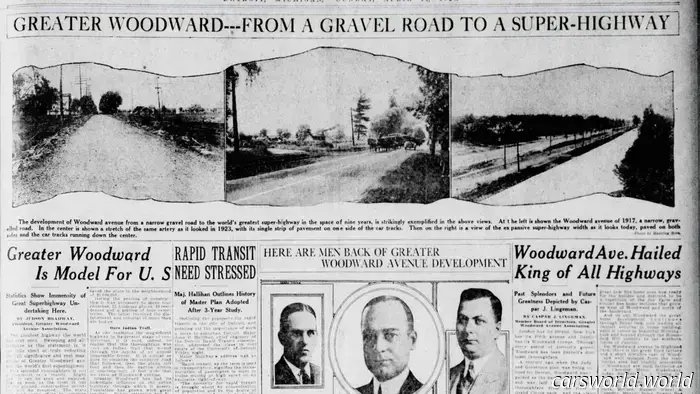

As Detroit expanded rapidly during the automotive boom of the 1910s and 1920s, city planners collaborated with regional partners to devise a plan that would fundamentally alter transportation for its residents. This ambitious vision was termed the superhighway, and it served as the cornerstone of what was arguably the most extensive regional mass transit system ever proposed in the United States.

Indeed, Southeast Michigan’s extensive grid of “Mile Roads” was designed not solely for private vehicle use, but as a comprehensive regional system that included surface rail, subways, streetcars, and automobiles. By the mid-1920s, Detroit’s rapid growth prompted planners to look far into the future. The city’s population was nearing one million, and some optimistic advocates were predicting it would exceed 10 million by 2000. Although that never materialized, Detroit residents sought broader roads as existing ones became increasingly congested with commuter traffic.

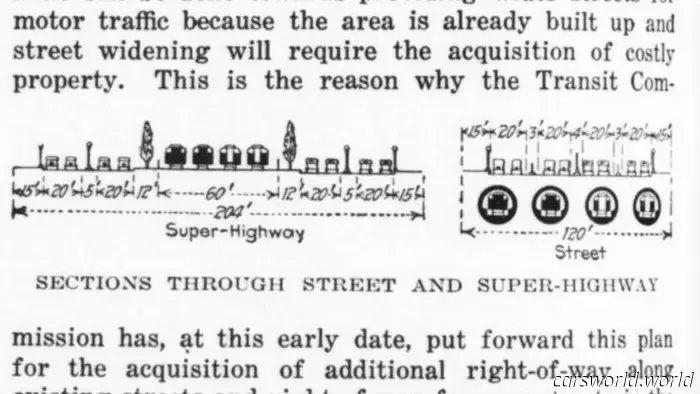

Local commissions supported the core ideas of the plan, leading to initiatives aimed at widening Detroit’s current avenues. The redesigned Mile Roads varied between 120 and 240 feet in width. The 120-foot roads could accommodate up to four subway lines beneath while leaving space for essential infrastructure like water and sewer systems; the 240-foot version allowed for four lanes of traffic in both directions, up to four rail lines (or a two-track station) in the center, all while leaving significant room for future expansions. Major arteries such as Woodward, Gratiot, and Grand River would serve as the connecting spokes in this vast new “superhighway” network, many of which integrated existing streetcar and inter-urban rail services seamlessly.

In contemporary times, the term “superhighway” has become less popular. Detroit’s initial prototypes included many elements commonly associated today with limited-access freeways—like wide medians and intersections with minimal conflicts—but were intended to remain accessible to surface vehicles and pedestrians as well.

The original plan specified that all significant mile-road intersections would be grade-separated interchanges (similar to highway cloverleafs but for surface streets), but this concept faded when officials realized the high costs involved. Consequently, only a select few intersections would receive such upgrades. Nowadays, many of the antiquated interchanges are being replaced with more cost-effective, low-conflict options, such as the recently completed diverging diamond at 8-Mile and Telegraph Road on the city’s border with Southfield.

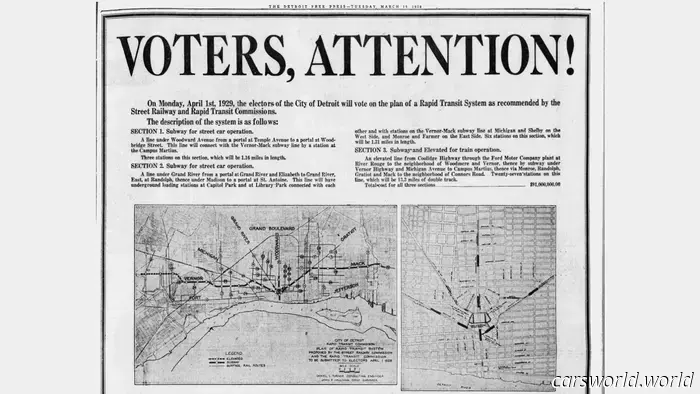

To compound the situation, the transit plan wouldn’t be voted on by Detroit until 1929—a year after the market crash that led to the Great Depression. The plan failed to pass the city council by a single vote. As speculation concerning the land along the highways dwindled and once-enthusiastic project advocates disappeared, southeastern Michigan’s planning bodies needed to devise more financially prudent ways to connect these major routes. After scaling back plans for flyover bridges, train stations, and subway tunnels, one remnant of this grand vision remained sensible.

The Michigan Left

It's a straightforward idea but executed brilliantly. Similar to New Jersey’s “jughandle,” the primary benefit of the Michigan Left is the removal of left turns at busy intersections. Instead of waiting to make a left turn against oncoming traffic, drivers turn right and then use a designated U-turn lane in the road's median to double back toward their intended direction. This setup not only shortens the wait time for left-turning vehicles but also enables traffic lights to cycle more quickly since through traffic doesn't have to pause for left turns.

The video above highlights Hall Road in Macomb County as an example, but due to Detroit’s early Superhighway plan, many Mile Roads had sufficient space to implement this arrangement. With timed traffic signals, these main arteries can operate similarly to the highways envisioned by their original designers, albeit without the integrated transit that justified the need for those wide medians in the first place.

Instead, what Detroit’s unsuccessful transit framework gave rise to was the earliest version of what we now refer to as a “Stroad”—a thoroughfare that blends characteristics of a street and a road. In urban planning terminology, a street is designed for mixed usage—

Other articles

Toyota has indeed created a RAV4 GR Sport featuring 320 horsepower, a tuned suspension, and summer tires.

Offered solely as a PHEV, the Toyota RAV4 GR Sport goes beyond being merely an appearance package.

Toyota has indeed created a RAV4 GR Sport featuring 320 horsepower, a tuned suspension, and summer tires.

Offered solely as a PHEV, the Toyota RAV4 GR Sport goes beyond being merely an appearance package.

Thieves Glimpsed Inside This V8 Wrangler and Fled Like Forrest Gump | Carscoops

Stolen vehicle recovery cars can provide a great bargain, and this Wrangler Rubicon 392 appears to be a solid choice, but that impression changes once you open the doors.

Thieves Glimpsed Inside This V8 Wrangler and Fled Like Forrest Gump | Carscoops

Stolen vehicle recovery cars can provide a great bargain, and this Wrangler Rubicon 392 appears to be a solid choice, but that impression changes once you open the doors.

Toyota's CEO States that the Company Can No Longer Sell Vehicles Solely Through Model Updates.

Toyota's CEO, Koji Sato, expresses his belief that for a car to be successful in today's tough market, it needs to be naturally enjoyable and resonate with people's passions.

Toyota's CEO States that the Company Can No Longer Sell Vehicles Solely Through Model Updates.

Toyota's CEO, Koji Sato, expresses his belief that for a car to be successful in today's tough market, it needs to be naturally enjoyable and resonate with people's passions.

This Plymouth Superbird was sold for $1.65 million in 2022. It recently fetched $418,000 at auction.

This Plymouth Superbird cost its seller over $1 million, as it was recently auctioned off for only a small portion of the amount they had originally paid.

This Plymouth Superbird was sold for $1.65 million in 2022. It recently fetched $418,000 at auction.

This Plymouth Superbird cost its seller over $1 million, as it was recently auctioned off for only a small portion of the amount they had originally paid.

Xiaomi Claims 10,000 Fake Accounts are Disseminating False Information About Its Electric Vehicles | Carscoops

The company asserts that a defamation campaign directed at them was revealed, leading to an investigation.

Xiaomi Claims 10,000 Fake Accounts are Disseminating False Information About Its Electric Vehicles | Carscoops

The company asserts that a defamation campaign directed at them was revealed, leading to an investigation.

Cash-Strapped Lotus Offers to Manufacture Polestar 6 Roadster

In this economy, everyone requires a second job, including Lotus.

Cash-Strapped Lotus Offers to Manufacture Polestar 6 Roadster

In this economy, everyone requires a second job, including Lotus.

Is the 'Michigan Left' the Solution to the Typical Stroad?

We explore how Detroit's most significant traffic innovation was developed from mass transit.